|

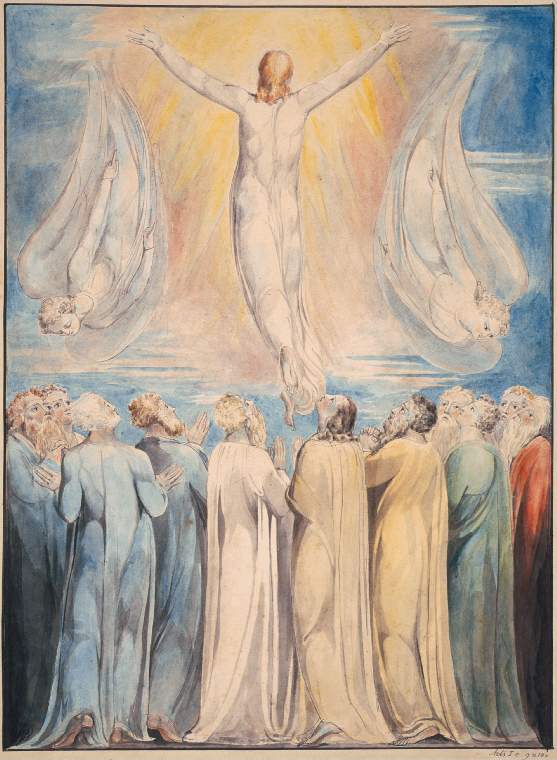

National Gallery of Art

Rosenwald Collection

The Pastorals of Virgil, 1821

Proof sheet printed by Blake |

Samuel Palmer was only 19 years old when he was introduced to William

Blake in 1824 by John Linnell. He remained under the influence of Blake 31 years later

when he wrote this letter to Alexander Gilchrist for inclusion in his

biography

The Life of William Blake. Palmer along with the other

'Ancients' admired Blake's woodcuts for Thornton's publication of

The Pastorals of Virgil.

From Samuel Palmer to Alexander Gilchrist:

"Kensington, Aug. 23d,

1855.

My Dear Sir,

I regret that the

lapse of time has made it difficult to recall many interesting

particulars respecting Mr. Blake, of whom I can give you no

connected account; nothing more, in fact, than the fragments of

memory; but the general impression of what is great remains with

us, although its details may be confused; and Blake, once known,

could never be forgotten.

His knowledge was

various and extensive, and his conversation so nervous and

brilliant, that, if recorded at the time, it would now have thrown

much light upon his character, and in no way lessened him in the

estimation of those who know him only by his works.

In him you saw at once

the Maker, the Inventor; one of the

few in any age: a fitting companion for

Dante. He was energy itself, and shed around him a kindling

influence; an atmosphere of life, full of the ideal. To walk

with him in the country was to perceive the soul of beauty

through the forms of matter; and the high gloomy buildings

between which, from his study window, a glimpse was caught of

the Thames and the Surrey shore, assumed a kind grandeur from

the man dwelling near them. Those may laugh at this who never

knew such an one as Blake; but of him it is the simple truth.

He was a man without

a mask; his aim single, his path straightforwards, and his wants

few; so he was free, noble, and happy.

His voice and manner

were quiet, yet all awake with intellect. Above the tricks of

littleness, or the least taint of affectation, with a natural

dignity which few would have dared to affront, he was gentle and

affectionate, loving to be with little children, and to talk

about them. "That is heaven," he said to a friend, leading him

to the window, and pointing to a group of them at play.

Declining, like Socrates, whom in many

respects he resembled, the common objects of ambition, and

pitying the scuffle to obtain them, he thought that no one could

be truly great who had not humbled himself " even as a little

child." This was a subject he loved to dwell upon, and to

illustrate.

His eye was the

finest I ever saw: brilliant, but not roving, clear and intent,

yet susceptible; it flashed with genius, or melted in

tenderness. It could also be terrible. Cunning and falsehood

quailed under it, but it was never busy with them. It pierced

them, and turned away. Nor was the mouth less expressive; the

lips flexible and quivering with feeling. I can yet recal it

when, on one occasion, dwelling upon the exquisite beauty of the

parable of the Prodigal, he began to repeat a part of it; but at

the words, "When he was yet a great way off, his father saw

him," could go no further; his voice faltered, and he was in

tears.

I can never forget

the evening when Mr. Linnell took me to Blake's house, nor the

quiet hours passed with him in the examination of antique gems,

choice pictures, and Italian prints of the sixteenth century.

Those who may have read some strange passages in his Catalogue, written in

irritation, and probably in haste, will be surprised to hear,

that in conversation he was anything but sectarian or exclusive,

finding sources of delight throughout

the whole range of art; while, as a critic, he was judicious

and discriminating.

No man more

admired Albert Diirer; yet, after looking over a number of his

designs, he would become a little angry with some of the

draperies, as not governed by the forms of the limbs, nor

assisting to express their action; contrasting them in this

respect with the draped antique, in which it was hard to tell

whether he was more delighted with the general design, or with

the exquisite finish and the depth of the chiselling; in works

of the highest class, no mere adjuncts, but the last

development of the design itself.

He united freedom

of judgment with reverence for all that is great. He did not

look out for the works of the purest ages, but for the purest

works of every age and country—Athens or Rhodes, Tuscany or

Britain; but no authority or popular consent could influence

him against his deliberate judgment. Thus he thought with

Fuseli and Flaxman that the Elgin Theseus, however full of

antique savour, could not, as ideal form, rank with the very

finest relics of antiquity. Nor, on the other hand, did the

universal neglect of Fuseli in any degree lessen his

admiration of his best works.

He fervently loved

the early Christian art, and dwelt with peculiar affection on

the memory of Fra Angelico, often speaking of him as an

inspired inventor and as a saint; but when he approached

Michael Angelo, the Last Supper of Da Vinci, the Torso

Belvidere, and some of the inventions preserved in the Antique

Gems, all his powers were concentrated in admiration.

When looking at the heads of the apostles

in the copy of the Last Supper at the Royal

Academy, he remarked of all but Judas,' Every one looks as if

he had conquered the natural man.' He was equally ready to

admire a contemporary and a rival. Fuseli's picture of Satan building the Bridge over Chaos he ranked with the

grandest efforts of imaginative art, and said that we were two

centuries behind the civilization which would enable us to

estimate his /Egisthus.

He was fond of the

works of St. Theresa, and often quoted them with other writers

on the interior life. Among his eccentricities will, no doubt,

be numbered his preference for ecclesiastical governments. He

used to ask how it was that we heard so much of priestcraft,

and so little of soldiercraft and lawyercraft.

The Bible, he said, was the book of liberty

and Christianity the sole regenerator of nations. In politics

a Platonist, he put no trust in demagogues. His ideal home was

with Fra Angelico: a little later he might have been a

reformer, but after the fashion of Savonarola.

He loved to speak

of the years spent by Michael Angelo, without earthly reward,

and solely for the love of God, in the building of St.

Peter's, and of the wondrous architects of our cathedrals. In

Westminster Abbey were his earliest and most sacred

recollections. I asked him how he would like to paint on

glass, for the great west window, his "Sons of God shouting

for Joy," from his designs in the Job. He said, after a

pause, "I could do it!" kindling at the thought.

Centuries could

not separate him in spirit from the artists who went about our

land, pitching their tents by the morass or the forest side,

to build those sanctuaries that now lie ruined amidst the

fertility which they called into being.

His mind was large

enough to contain, along with these things, stores of classic

imagery. He delighted in Ovid, and, as a labour of love, had

executed a finished picture from the Metamorphoses, after

Giulio Romano. This design hung in his room, and, close by his

engraving table, Albert Diirer's Melancholy the Mother of Invention, memorable as

probably having been seen by Milton, and used in his Penseroso. There are

living a few artists, then boys, who may remember the smile of

welcome with which he used to rise from that table to receive

them.

His poems were

variously estimated. They tested rather severely the

imaginative capacity of their readers. Flaxman said they were

as grand as his designs, and Wordsworth delighted in his Songs 0/ Innocence. To the

multitude they were unintelligible. In many parts full of

pastoral sweetness, and often flashing with noble thoughts or

terrible imagery, we must regret that he should sometimes have

suffered fancy to trespass within sacred precincts.

Thrown early among the authors who resorted

to Johnson, the book-seller, he rebuked the profanity of

Paine, and was no disciple of Priestley; but, too

undisciplined and cast upon times and circumstances which

yielded him neither guidance nor sympathy, he wanted that

balance of the faculties which might have assisted him in

matters extraneous to his profession. He saw everything

through art, and, in matters beyond its range, exalted it from

a witness into a judge.

He had great

powers of argument, and on general subjects was a very patient

and good-tempered disputant; but materialism was his

abhorrence: and if some unhappy man called in question the

world of spirits, he would answer him "according to his

folly," by putting forth his own views in their most

extravagant and startling aspect. This might amuse those who

were in the secret, but it left his opponent angry and

bewildered.

Such was Blake, as I remember him. He was

one of the few to be met with in our passage through life, who

are not, in some way or other, "double minded " and

inconsistent with themselves; one of the very few who cannot

be depressed by neglect, and to whose name rank and station

could add no lustre. Moving apart, in a sphere above the

attraction of worldly honours, he did not accept greatness,

but confer it. He ennobled poverty, and, by his conversation

and the influence of his genius, made two small rooms in

Fountain Court more attractive than the threshold of princes.

I remain, my dear

Sir,

Yours very

faithfully,

Samuel Palmer. To

Alexander Gilchrist, Esq."

.