_object_45_The_Little_Vagabond.jpg) |

Fitzwilliam Museum Songs of Innocence and of Experience Plate 45,Copy AA |

What he Said

In 'Songs of Experience' Blake expressed some biting truths about the place of the church in the lives of ordinary people:

"A

little black thing among the snow,

Crying "'weep! 'weep!" in notes of

woe!

"Where are thy father & mother? Say?"

They are both gone up to

the church to

pray. Because I was happy upon the heath,

And

smil'd among the winter's snow,

They clothed me in the clothes of

death,

And taught me to sing the notes of woe.

And because I

am happy & dance & sing,

They think they have done me no injury,

And are gone to praise God & his Priest & King,

Who

make up a heaven of our misery."

(The Chimney Sweeper from Songs of Experience, Song 37, (E 22))

Surely the church has become more human since Blake's day, when it

could condone the employment of five year olds as chimney sweepers and

in fact their legal sale by their parents for such a purpose. Even more

bald in its

ecclesiastical implications is The Little Vagabond, which

sounds very much like a Ranter's song:

"Dear Mother, dear Mother, the Church is cold,

But the Ale-house is healthy & pleasant & warm;

Besides I can tell where I am used well,

Such usage in heaven will never do well.

But if at the Church they would give us some Ale,

And a pleasant fire our souls to regale,

We'd sing and we'd pray all the live-long day,

Nor ever once wish from the Church to stray.

Then the Parson might preach, & drink, & sing,

And we'd be as happy as birds in the spring;

And modest dame Lurch, who is always at Church,

Would not have bandy children, nor fasting, nor birch.

And God, like a father rejoicing to see

His children as pleasant and happy as he,

Would have no more quarrel with the Devil or the Barrel,

But kiss him, & give him both drink and apparel."

(The Little Vagabond, Song 45, (E 26) )

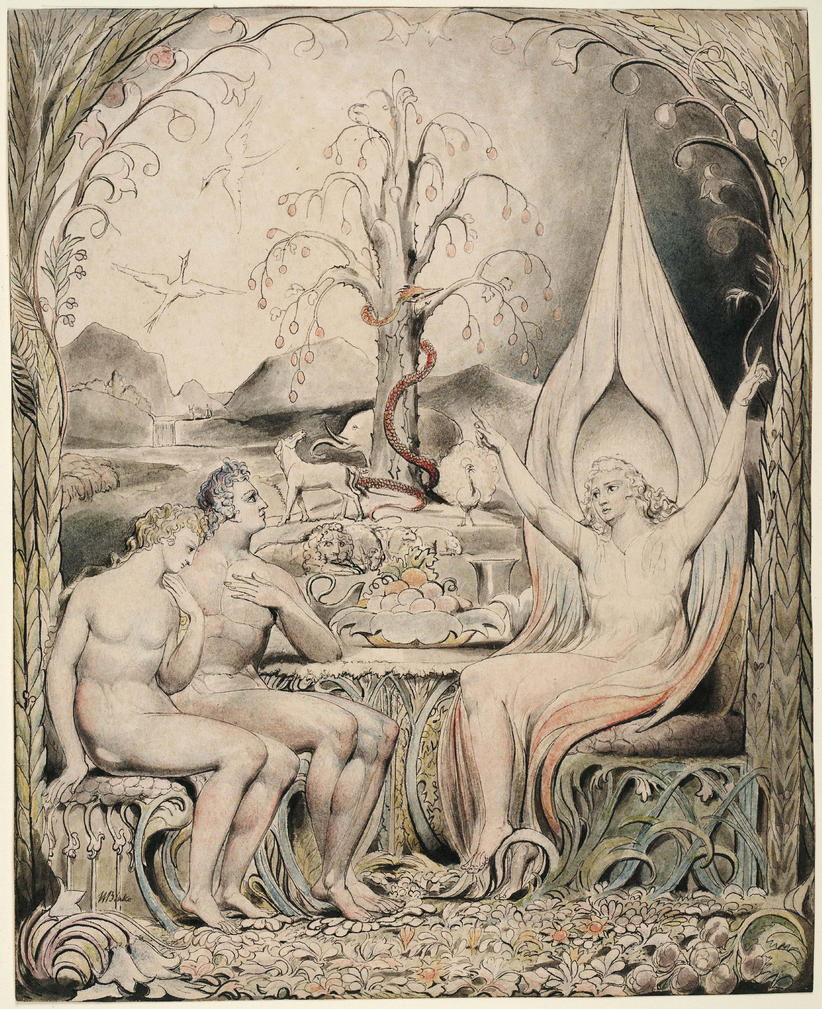

In Europe, written about the same time, Blake recounts the degradation of the church with the cult of chivalry and the Queen of Heaven:

"Now comes the night of Enitharmon's joy!

Who shall I call? Who shall I send,

That Woman, lovely Woman, may have dominion?

Arise, O Rintrah, thee I call! & Palambron, thee!

Go! tell the Human race that Woman's love is Sin;

That an Eternal life awaits the worms of sixty winters

In an allegorical abode where existence hath never come.

Forbid all Joy, & from her childhood shall the little female

Spread nets in every secret path."

(Europe 5:1ff, (E 62) )

Enitharmon's grammar in the second line indicates her essential falsity,

assuming the place of the true God (See Isaiah 6

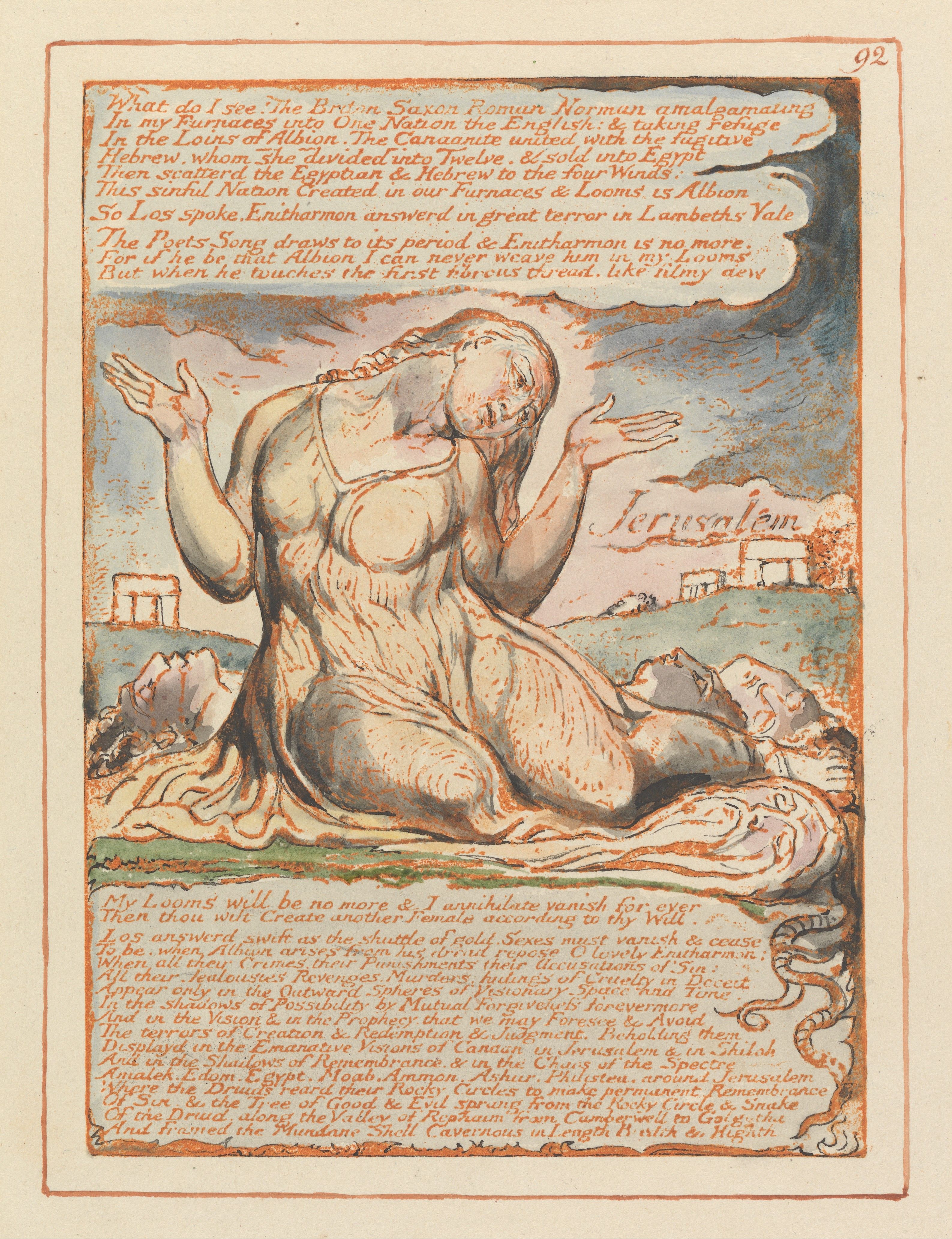

). But after 1800 Blake

rehabilitates Enitharmon, and Rahab becomes his

symbol of the false church;

she continually afflicts Jerusalem and

finally crucifies Jesus (See 4Z and J).

Blake used the word

'church' in some rather unconventional ways. In Milton,

Plate 37 and

later in 'Jerusalem' Plate 76 he divided human history into 27

Churches,

made up of three groups. The first corresponds to the nine

antediluvian

patriarchs (Adam to Lamech) taken from Genesis 5. The second

group

includes the patriarchs from Noah to Terah, the father of Abraham. For

the third series Blake chose seven famous religious leaders from Abraham

to

Luther; each of these represents for Blake a certain type or phase

of religious

history:

The first two groups were druidic (devoted to cultic murder), but Abraham

began to curtail human sacrifice when he chose a ram instead of Issac (See

Genesis 22

). Moses brought the Law; Solomon represents Wisdom. Paul

represents

the early Christian Church. Constantine marks its embrace by the

highest

satanic power. Charlemayne founded the Holy Roman Empire, and

Luther

brings us to the modern age. All of these except Paul resorted to war;

therefore Blake referred to these Churches as "Religion hid in war".

Blake felt that he had described a natural progression going nowhere

for

"where Luther ends, Adam begins again in Eternal Circle", but this

"Eternal

Circle" is interrupted by Jesus, who, "breaking thro' the

Central zones of Death & Hell,/ Opens Eternity in Time & Space,

triumphant in Mercy". There in its most concentrated form is Blake's

6000 year history of the church.

Bear in mind that 27 is a super sinister number; Frye

described it as "the

cube of thee, the supreme aggravation of three". A

happier constellation of 28 (a composite of the complete numbers four

and seven) occurs in Jerusalem where England's cathedral cities are

called the Friends of Albion. With this image Blake recognized that in

spite of all its sins the church had exercised a beneficent influence

upon the course of history. Blake habitually picked one of these cities to represent an important historical personage.

For

example Ely, the cathedral city of Cambridgeshire, stands for Milton,

the greatest man produced by Cambridge. Verulam, an ancient name for

Canterbury, represents Francis Bacon , one of Blake's chief devils.

Professor

Erdman informed us that Bath represents Rev. Richard Warner, a

courageous

minister who preached against war in 1804, when to do such a

thing bordered

on sedition. Blake's admiration for Warner led to the

prominence which he gave Bath in the second chapter of Jerusalem.

Aside from these prophetic and poetic excursions the Blakean doctrine of

the church found in the myth is roughly as follows: The Church is Beulah. The

majority of the population exist beneath it, spiritually asleep, living what Blake

called Eternal Death without even a murmur of discontent. Their eyes

are closed to the spirit. They are seeds that do not generate. The

hungry generally take refuge in a church and surrender their spiritual

destiny into the keeping of a priest or a priestly community.

A few still suffer hunger and eventually may come out into the sunlight .

That chosen few are, like Blake, compelled to live in a state of tension with the

church that belongs to the world. The best of them continually court

martyrdom and may be honored posthumously if at all. But of such is the

kingdom of heaven, where like Blake they cast off the enslavement of

other men's systems and create their own.

(Nels Ferre, who may or may not have known Blake, wrote a short parable

that describes the Blakean doctrine of the church as well or better than

Frye did. It appears in the beginning of a small book entitled The Sun and the Umbrella. The image of the church as an umbrella keeping us from the full force of the Sun is compelling and quite Blakean.

(See also Religion and War)