A post published by Larry in 2009 and expanded by ellie.

People interested in Blake are more apt to read about

Blake than to read Blake. Reading The Four Zoas,

Milton, and Jerusalem are awesome undertakings. Until

you've begun to understand the man's language, it's

a losing proposition. There's a core set of metaphors

that he used repeatedly, although like all metaphors

his are subject to various interpretations, and often

used for an object or its opposite.

To enable intelligent reading of the major prophecies there is a great abundance of commentary on his works. Where does one begin? Those of us who have made a few steps in that direction can perhaps give a bit of guidance to the beginning student.

Northrup Frye's Fearful Symmetry was the work that made me a life long lover of Blake's poetry. It's not easy; I read it five times before I was able to get more than a few glimmers of light. But it's very rewarding; you're likely smarter than me, in which case one or two readings may get you well into the long poems.

Frye was a minister of the United Church of Canada as well as celebrated literature critique; after finishing Fearful Symmetry he said that if he had it to do over, he would have written more of an introduction than what he actually did. But more than a half century after it was published Fearful Symmetry is introducing serious readers to an experience of discovery:

"Blake's cosmology, of which the symbol is Ezekiel's vision of the chariot of God with its 'wheels within wheels,' is a revolutionary vision of the universe transformed by the creative imagination of a human shape. This cosmology is not speculative but concerned, not reactionary but revolutionary, not a vision of things as they are ordered but of things as they could be ordered...Blake's poetry, like that of every poet who knows what he is doing, is mythical, for myth is the language of concern: it is cosmology in movement, a living form not a mathematical one." (Preface)

The one who gave the simplest introduction for me was Milton Percival in William Blake's Circle of Destiny; it's more systematic and more elementary. Percival connects the myth Blake created with literature which fed its development:

"I predict, then, that when the evidence is in, it will be found that in the use of tradition Blake exceeded Milton, and was second, if to anyone, only to Dante. To be sure, a great deal of the Blakean tradition might not be called 'accepted.' It certainly was not orthodox. But the Blakean heterodoxy was equally traditional with Dante's orthodoxy. The Orphic and Pythagorean tradition, Neoplatonism in the whole of its extent, the Hermetic, kabbalistic, Gnostic, and alchemical writings, Erigena, Paracelsus, Boehme, and Swedenborg - here is a consistent body of tradition extending over nearly twenty-five hundred years. In the light of this tradition, not the light of Christian orthodoxy, Blake read his Bible, weighing and deciding for himself, formulating a 'Bible of Hell'; for he was one in whose veins ran the dissidence of dissent and the protestantism of the Protestant religion." (Page 1)

But Kathleen Raine's Blake and Tradition was what made me a real enthusiast. That's the most easily readable one, and it's filled with some of Blake's loveliest pictures. Unfortunately Blake and Tradition is out of print now, but a fairly good substitute may be found in her little book, Blake and Antiquity or in her biography titled William Blake. Raine sees the whole of Blake's art enmeshed in the tradition which it expands:

"Blake was such an artist; and his work, as he believed, represents 'portions of Eternity' seen in imaginative vision. Blake himself writes of 'ever Existent Images' which may be seen 'by the Imaginative Eye of Every one according to the situation he holds' - a collective archetypal world whose reality is more credible in our century that it was in his own. 'To different people it appears differently, as everything else does.' Such art comes from a source deeper than the individual experience of poet or painter, and has the power of communication to that same level of the spectator. To our superficial selves this is a source of the 'obscurity' of visionary art; to our deepest selves, of its lucidity." (Page 7)

|

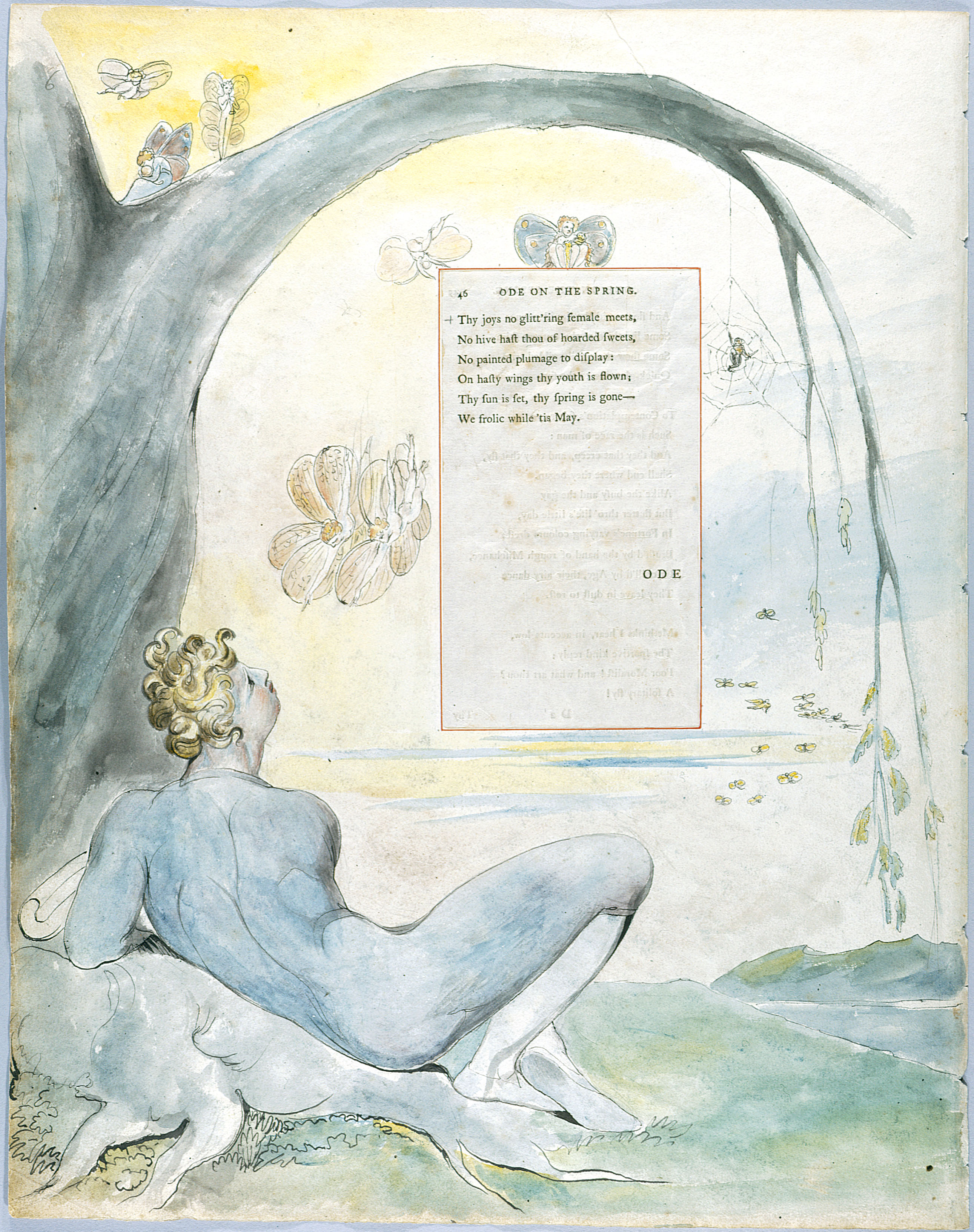

| Wikimedia Commons Blake's Watercolors for Poems of Thomas Gray Ode to Spring, Page 6 |

To enable intelligent reading of the major prophecies there is a great abundance of commentary on his works. Where does one begin? Those of us who have made a few steps in that direction can perhaps give a bit of guidance to the beginning student.

Northrup Frye's Fearful Symmetry was the work that made me a life long lover of Blake's poetry. It's not easy; I read it five times before I was able to get more than a few glimmers of light. But it's very rewarding; you're likely smarter than me, in which case one or two readings may get you well into the long poems.

Frye was a minister of the United Church of Canada as well as celebrated literature critique; after finishing Fearful Symmetry he said that if he had it to do over, he would have written more of an introduction than what he actually did. But more than a half century after it was published Fearful Symmetry is introducing serious readers to an experience of discovery:

"Blake's cosmology, of which the symbol is Ezekiel's vision of the chariot of God with its 'wheels within wheels,' is a revolutionary vision of the universe transformed by the creative imagination of a human shape. This cosmology is not speculative but concerned, not reactionary but revolutionary, not a vision of things as they are ordered but of things as they could be ordered...Blake's poetry, like that of every poet who knows what he is doing, is mythical, for myth is the language of concern: it is cosmology in movement, a living form not a mathematical one." (Preface)

The one who gave the simplest introduction for me was Milton Percival in William Blake's Circle of Destiny; it's more systematic and more elementary. Percival connects the myth Blake created with literature which fed its development:

"I predict, then, that when the evidence is in, it will be found that in the use of tradition Blake exceeded Milton, and was second, if to anyone, only to Dante. To be sure, a great deal of the Blakean tradition might not be called 'accepted.' It certainly was not orthodox. But the Blakean heterodoxy was equally traditional with Dante's orthodoxy. The Orphic and Pythagorean tradition, Neoplatonism in the whole of its extent, the Hermetic, kabbalistic, Gnostic, and alchemical writings, Erigena, Paracelsus, Boehme, and Swedenborg - here is a consistent body of tradition extending over nearly twenty-five hundred years. In the light of this tradition, not the light of Christian orthodoxy, Blake read his Bible, weighing and deciding for himself, formulating a 'Bible of Hell'; for he was one in whose veins ran the dissidence of dissent and the protestantism of the Protestant religion." (Page 1)

But Kathleen Raine's Blake and Tradition was what made me a real enthusiast. That's the most easily readable one, and it's filled with some of Blake's loveliest pictures. Unfortunately Blake and Tradition is out of print now, but a fairly good substitute may be found in her little book, Blake and Antiquity or in her biography titled William Blake. Raine sees the whole of Blake's art enmeshed in the tradition which it expands:

"Blake was such an artist; and his work, as he believed, represents 'portions of Eternity' seen in imaginative vision. Blake himself writes of 'ever Existent Images' which may be seen 'by the Imaginative Eye of Every one according to the situation he holds' - a collective archetypal world whose reality is more credible in our century that it was in his own. 'To different people it appears differently, as everything else does.' Such art comes from a source deeper than the individual experience of poet or painter, and has the power of communication to that same level of the spectator. To our superficial selves this is a source of the 'obscurity' of visionary art; to our deepest selves, of its lucidity." (Page 7)

Vision of Last Judgment, (E 560)

"If the Spectator could Enter into these Images in his

Imagination approaching them on the Fiery Chariot of his

Contemplative Thought if he could Enter into Noahs Rainbow or

into his bosom or could make a Friend & Companion of one of these

Images of wonder which always intreats him to leave mortal things

as he must know then would he arise from his Grave then would he

meet the Lord in the Air & then he would be happy General

Knowledge is Remote Knowledge it is in Particulars that Wisdom

consists & Happiness too. Both in Art & in Life General Masses

are as Much Art as a Pasteboard Man is Human Every Man has Eyes

Nose & Mouth this Every Idiot knows but he who enters into &

discriminates most minutely the Manners & Intentions the

Expression of Character in all their branches is the

alone Wise or Sensible Man & on this discrimination All Art is

founded. I intreat then that the Spectator will attend to the

Hands & Feet to the Lineaments of the Countenances they are all

descriptive of Character & not a line is drawn without intention

& that most discriminate & particular as Poetry admits not a

Letter that is Insignificant so Painting admits not a Grain of

Sand or a Blade of Grass much less an Insignificant Blur or Mark"

.

No comments:

Post a Comment