First published Dec 27, 2013. This is a section of Larry's online book: A Blake Primer.

Sin and Forgiveness

"Whosoever of you are justified by the law: ye are fallen from grace"

Just

as he redefined hell, so Blake redefined sin. The only sin for Blake

consisted in hindering, oneself or another: "Murder is Hindering Another, Theft is Hindering Another."(Annotations to Lavater, E 601) To subvert one's individuality is the sin against the Holy Spirit. "He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence".

The

responsibility for hindering another falls upon the Lawmaker and

Enforcer, who has polluted life with his prohibitions: "over the doors

Thou shalt not". One could say that Blake took Paul's letters to the Romans

and to the Galatians too seriously. Luther had taken those epistles

seriously enough to throw off the Roman yoke. Blake took them more

radically and threw off the mosaic yoke--as Paul had suggested.

Paul had identified the Law with the flesh and opposed it with the Spirit. Our poet took with utmost seriousness these stirring passages calling the Christian to freedom from the Law. He didn't have the benefit of the 'interpretations' of such ideas afforded by the educational process. Sin stems from our ideas of morality, which Blake called hindering. When we presume to know what someone else should or must do, we have entered the state of Caiaphas, the Pharisee, who crucified Jesus, but "was in his own Mind a benefactor to Mankind."

The

categories of sin and righteousness divide mankind. The division often

proceeds to the point of physical violence. Corporeal war always rests

upon a base of self-righteousness and condemnation of the sins of the

enemy. Religion too often allies itself with those attitudes and their

violent results. Long before the peaceniks of the sixties Blake said in

effect, "Make love, not war!" He said it at great length in dozens of

different ways. He saw war as the ultimate end of hindering another. In

the Book of Urizen we

read how Urizen, the great Lawgiver (who lives in all of us!) discovers

that none of his children can obey his laws, "for he saw that no flesh

nor spirit could keep His iron laws one moment".

If we can suspend our judgements about people's conduct and stop tormenting ourselves because of our failures to do the good which we have laid upon ourselves, if we can accept what we have called bad, but which may be simply disowned facets of our true nature, in Blake's terminology if we can forgive, then we can put sin behind us and receive the gift of eternal life. Blake, drinking deeply from the primary fountains of scripture, intuitively expressed these universal truths in poetic terms. (100 years later Jung came along and clothed them with the respectability of a scientific jargon.)

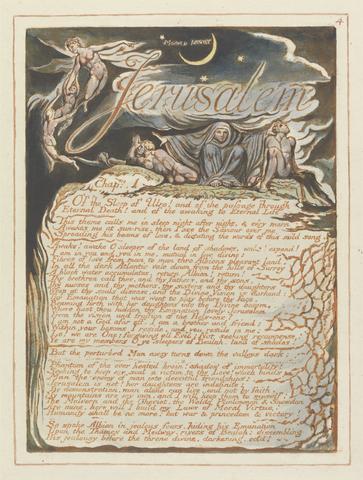

Jerusalem,

Blake's symbol of the redeemed and pure consciousness, speaking to

Vala, his symbol of the fallen mind, expressed Blake's candid evaluation

of Sin as such: "Oh Vala...what is sin but a little error & fault

that is soon forgiven?" (Jerusalem 20:23-25)

If the primary moral wrong is hindering, the primary grace is forgiveness. Redemption came for Blake when forgiveness first entered the horizon of his vision; it increasingly came to dominate it. Prior to 1800 with all his denunciations of Urizen, the Restrainer, and of morality Blake was growing more and more into the role of judge. He was becoming in fact a judge of judges. The later Lambeth books witness the resultant decrease in vitality; in the language of Zion he suffered a loss of faith. It coincided with a slowly dawning realization that Urizen had infested his own mind all the while he was denouncing him in others. There awakened in his mind a new awareness of sin, a sin more basic than hindering others, or rather an awareness of the inner cause of hindering. He called it the Selfhood, the Spectre, Satan. As many of us have since that day, Blake realized that he saw the God-playing in others because he was so good at it himself. This new vision of his Selfhood led to the Moment of Grace.

At Felpham, in the major crisis of his life, he faced the need to forgive both the impositions of his corporeal friend, Hayley, and the resentful thunderer, William Blake, as well. The appearance of his first Vision of Light marks the coming of Christ into his life with the power of this forgiveness; henceforth he called him Jesus, the Forgiveness.

The old Urizenic monstrosity that had haunted him, first in the outer world and increasingly as a component of his own psyche, was recognized, accepted, subdued, and forgiven. It was undoubtedly the greatest event of his life, a new birth of hope at the age of 43. He shared with us the psychic unfolding of this experience in Night vii of The Four Zoas where Los embraces his Spectre (equivalent to Jung's acceptance of the shadow) and soon thereafter finds Urizen miraculously changed:

Four Zoas, Night VII, Page 98 [90], (E 371)

"But Tharmas most rejoicd in hope of Enions return

For he beheld new Female forms born forth upon the air

Who wove soft silken veils of covering in sweet rapturd trance

Mortal & not as Enitharmon without a covering veil

First his immortal spirit drew Urizen[s] Shadow away

From out the ranks of war separating him in sunder

Leaving his Spectrous form which could not be drawn away

Then he divided Thiriel the Eldest of Urizens sons

Urizen became Rintrah Thiriel became Palamabron

Thus dividing the powers of Every Warrior

Startled was Los he found his Enemy Urizen now

In his hands. he wonderd that he felt love & not hate

His whole soul loved him he beheld him an infant

Lovely breathd from Enitharmon he trembled within himself"

Has

anyone better portrayed the psychodynamics of forgiveness? In order to

forgive you first withdraw the projection, then you forgive yourself.

It's your baby!

We

can't say that's the end of the story; in Night viii Urizen continues

to afflict life with his judgements, hostility and violence; Satan comes

forth from his War. The Saviour dies for him, and we are still waiting

for the ultimate victory. Nor was Blake himself fully delivered from the

resentments and self justifications of the old man. Hard times ahead,

the deceitfulness and opprobrium of others continued to afflict and to

warp his psyche and caused him to participate in sin (mostly by

suffering through the sins of others against him), but now he knew the

answer: through recurring awareness and Self-annihilation he could

forgive again and again. The wheat and tares continued to grow together.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment