The Two Women

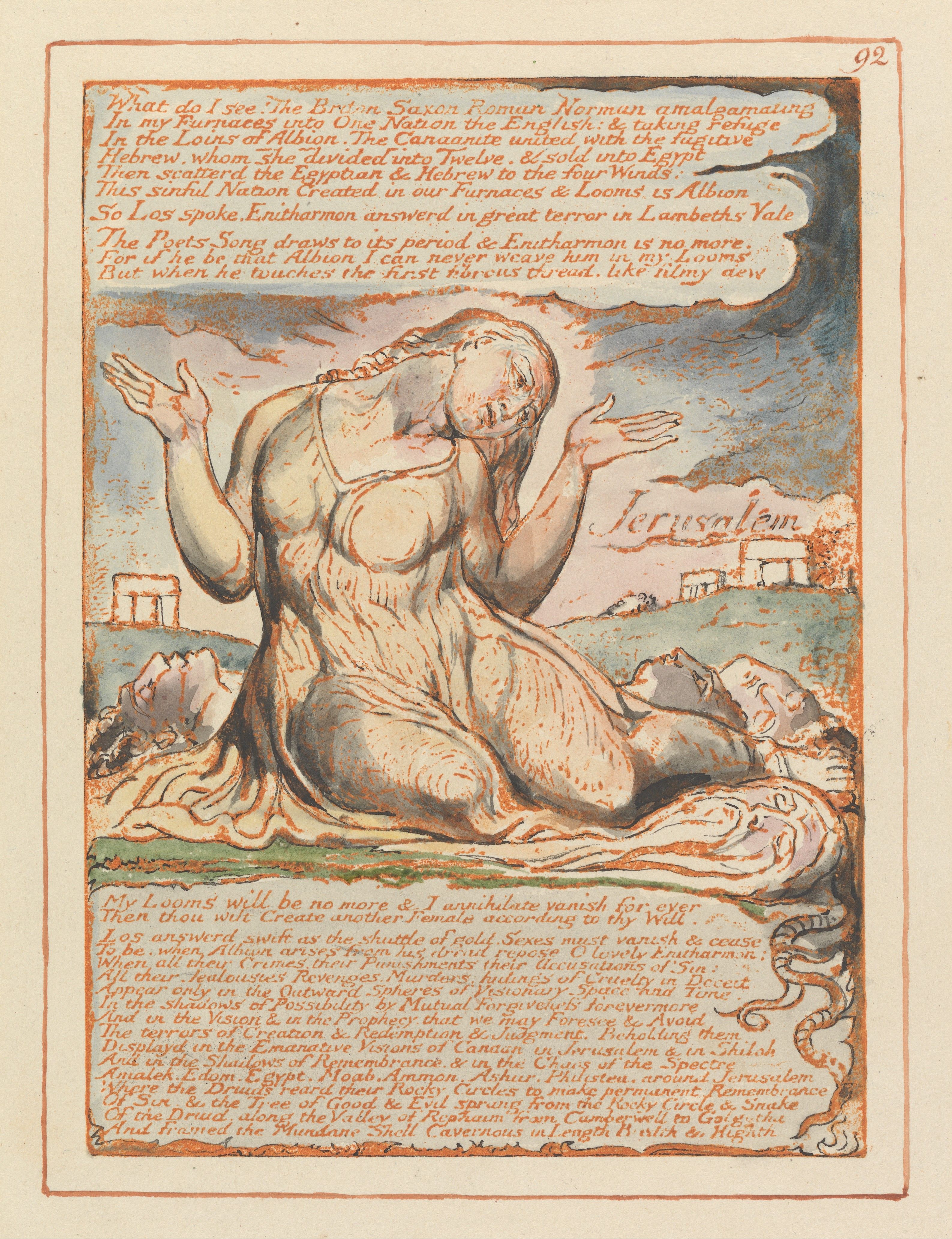

When Blake began to work on his epic myth, he intended to focus upon the wicked career of Vala, but as time went by, he became more interested in the Zoas, which no doubt helped to relieve the anti-feminine bent of his metaphysics. Vala temporarily sank to the level of a minor character, and Blake laid most of the guilt for man's sorry state upon Urizen. The Moment of Grace brought another significant change: Vala fumed into two females, Rahab and Jerusalem, both of whom issue from Enitharmon.When Blake gave Rahab the alternate name of Babylon, he came into conformance with the basic symbology of the Bible. Throughout the scripture we read about these two women/cities. Jerusalem is at least potentially the city of God, while Babylon always represents the seat of the God of this World. In his last epic Blake's Vala has become virtually interchangeable with Babylon.

We have already noted the biblical sources of Blake's two symbolic women in the 12th and 17th chapters of Revelation. In the first of these John sees a woman "clothed with the sun and the moon under her feet". In the second he described "the great whore that sitteth upon many waters". These two women in the Bible aptly prefigure Blake's Jerusalem and Vala, and a careful study of the two chapters will help the reader to shape in his own mind the identity of Blake's two characters.

John and Blake both drew their paired women from earlier sources. Frye calls them "royal metaphors" for the twin totalities of good and evil, of redemption and damnation that fill the pages of the Bible. The Tower of Babel, the first city of sin, led to the confusion of tongues. Following God's command Abraham, the father of the Hebrews, left Ur, a few miles from Babylon and eventually settled in the Promised Land. The first Captivity occurred in Egypt, which later biblical literature often treats as synonymous with Babylon. The second Captivity took place at Babylon. A later captivity was to Rome, which John the Apocalyptist called Babylon: in Revelation he celebrated the burning of the Whore of Babylon.

Meanwhile Melchizidek, King of Salem and priest of the Most High God, had blessed Abraham. Some centuries later David established Jerusalem as his capital. The Song of Solomon is a poem and love song about a king and his bride. This theme became a primary symbol of the relation between Jerusalem, representing the Chosen People, and God. The prophets constantly referred to Jerusalem as a woman, married to God, but too often faithless, whoring after other gods. Hosea's stories about the love of the betrayed husband for his faithless wife, Gomer, poetically express the highest level of the Hebrew consciousness of God. On occasion the prophets became so enraged that they identified Jerusalem with Babylon. For example John spoke of "the great city which spiritually is called Sodom and Egypt, where also our Lord was crucified".

This biblical background prepares us to cope with the woman found in Blake's poem, Jerusalem . As we have seen, in the poetry of the first half of Blake's life the woman is sinister. She represents the material; the material is unworthy, reprehensible, satanic. This is the typical Gnostic position and to a lesser extent the Neo-platonic position. Blake stated it very explicitly and with his usual hyperbole in 'Visions of the Last Judgment' (E 565) (See also the image): "I assert for My Self that I do not behold the outward Creation & that to me it is hindrance and not Action; it is as the Dirt upon my feet. No part of Me."

He wrote that as late as 1810. Nevertheless after the Moment of Grace Blake's perspective on matter (and Woman!) softened. At first there had been only the sinister woman, but now the Woman of Grace appeared as well.

In the poem, Jerusalem, we find a discourse and a conflict between these two women. Vala speaks for the kingdom of Satan, and Jerusalem speaks for the kingdom of Heaven. Their interaction dominates the poem and must fascinate anyone interested in those two subjects. The epic is a straightforward conflict between light and darkness as Blake understood those two realities. Vala wins most of the battles, but we always know who must win the war.

Blake describes reality imaginatively and dramatically in terms of ultimate value; this is basically an expression of faith. If one believes in the higher values: in spirit, in truth, in justice and love, then one imagines these things ultimately victorious. Blake did, and he concluded the passage from VLJ quoted above: "What, it will be Question'd, 'When the Sun rises, do you not see a round disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?' 0 no, no, I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying 'Holy, holy, Holy is the Lord God Almighty.'" In Blake's final epic Vala represents the guinea sun and Jerusalem the "innumerable company of the Heavenly host". Needless to say those who see only the guinea sun will not be attracted to the poem.

vi

'Jerusalem'

At the very beginning of Blake's poem, Jerusalem, he makes us fully aware that the new woman represents something entirely other than the disreputable matter of earlier writing. She is just the opposite; she is Spirit or rather the manifestation of Spirit in this world. The Saviour confronts the sleeping Albion and identifies his disease, "where hast thou hidden thy Emanation, lovely Jerusalem". But the "perturbed Man" denies Christ and denies Jerusalem: "Jerusalem is not! her daughters are indefinite: By demonstration man alone can live, and not by faith." A few lines further the poet announces that

The place names represent the six heathen nations or the powers of evil that surround the Chosen People. The import of all this in another biblical phrase is that "He who departs from evil makes himself a prey".

Very shortly we meet the Daughters of Albion; they represent the feminine dimension of the materialistic impulses of Man: "Names anciently remember'd, but now contemn'd as fictions. Although in every bosom they controll our Vegetative powers". Eventually a redemptive moment occurs when, Los having subdued and integrated his Spectre, his Sons and Daughters "come forth from the Furnaces". Erin, like America a symbol of redemption, addresses Jerusalem:

In an extended passage too long to quote here Blake gives a colloquy with the fainting, confused Albion and the two females competing for his heart. It's actually a recreation of the earlier colloquy in VDA, and infinitely richer and fuller. Albion wavers exactly like Theotormon; Vala, like Bromion, is implacably blind, and Jerusalem has the eloquence of the earlier heroine. In this scene, like the earlier one, Blake describes the eternal battle between faith and worldliness.

Look also at the passage on Plates 32-34 and remember that Albion, Vala and Los each speaks from his own viewpoint. To understand Blake's vision the reader must imaginatively enter the psychic state of each of the three characters. Los most often speaks from the poet's true standpoint, and the following lines put his position about as plainly as it can be put:

As the third chapter of Jerusalem begins, Blake describes Jerusalem for us once more:

Blake's ethics of sexual love, his symbolism, and his Christian faith all fit together and reach a climax in a sketch virtually guaranteed to astound and provoke the reader (and no doubt dismay and disgust some). This passage, Plates 61 and 62, is called "Visions of Elohim Jehovah". Here once again forgiveness is the key, and to Blake forgiveness was everything. Vala, the soul of materialism, knows nothing of forgiveness. Jerusalem's liberty is expressed most fully in forgiveness. In this passage Mary, the mother of Jesus, merges with the other Mary, who was forgiven because "she loved much".

"Visions of Elohim Jehovah" could only have been written by a poet who despised the social value placed upon virginity. In an earlier work he had called it "pale religious letchery that wishes but acts not". Blake hated the ideal of chastity, which meant to him a virtuous withholding of woman's body as an exercise of power over the deprived male, and he struck directly at the archetype of the chaste woman. "Visions of Elohim Jehovah" is not a theological statement, but an imaginative vision about meaning and value. The love of Blake will always be confined to people who discriminate between those two things and whose theological perspective is neither glassy eyed nor otherwise rigid.

Blake's Mary has perfect trust in the forgiveness of sin, and her relationship with Joseph becomes a type for the relationship of Jerusalem with Jesus:

The allegoric drama of good and evil in terms of the two females continues and intensifies throughout the epic poem until the final awakening of Albion, when sexes disappear. The first indication of this is in the dialogue of Los and Enitharmon:

Soon comes the last mention of the woman of the world. She is connected with her sexual counterpart and described in the very specific terms which John used in Revelation 17:

And after the final chorus of the multiple aspects of Man, Blake tells us that he "heard the Name of their Emanation: they are named Jerusalem." And so ends Jerusalem.

| ||

No comments:

Post a Comment