|

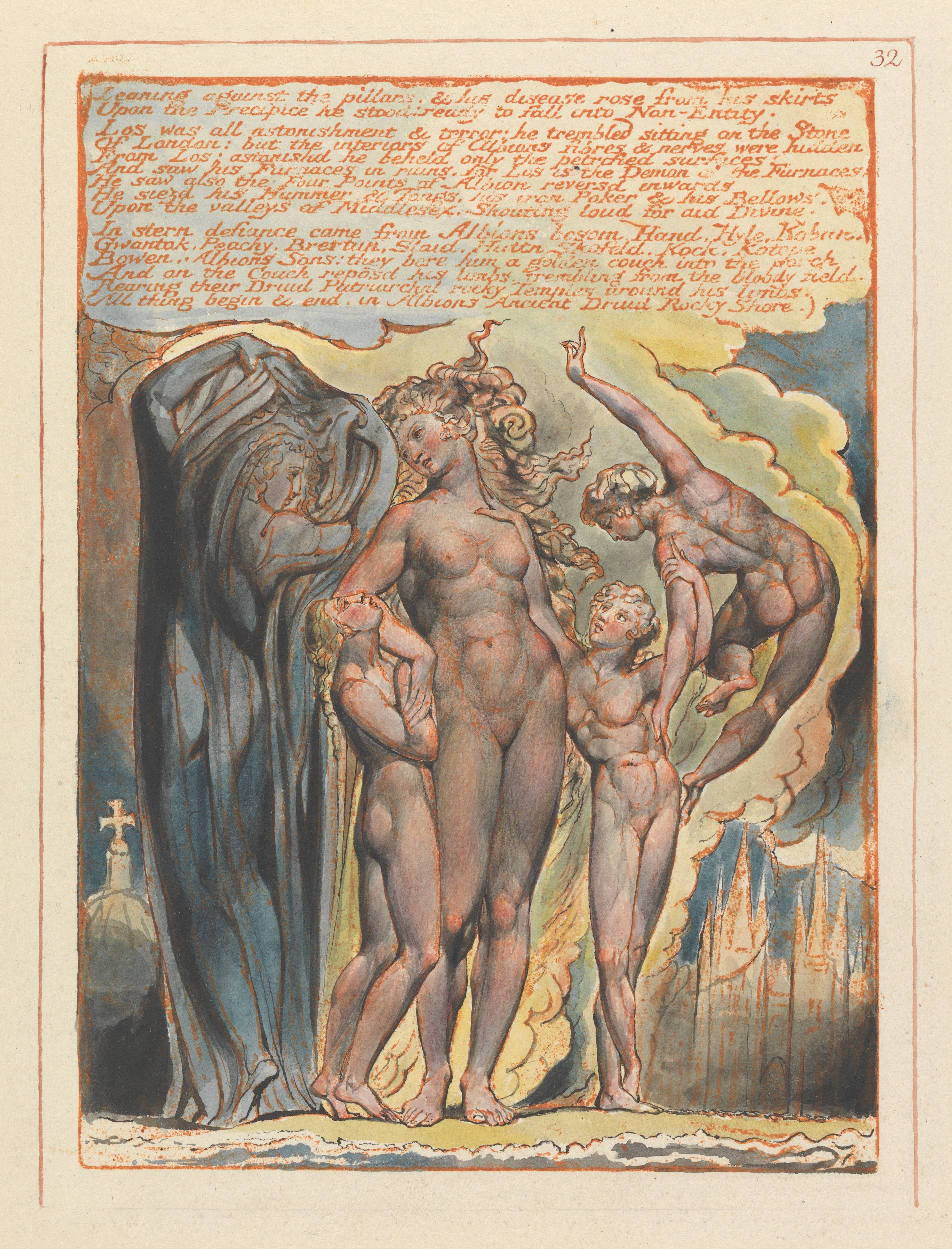

Yale Center for British Art Jerusalem Plate 32 |

Poetry by its nature yields meaning at more than one level. Most of Blake's poetry has significance at three primary levels: (1) political or historical, (2) personal or psychological, and (3) religious or metaphysical. Blake would have denied these distinctions because life to him was all one.

He saw the political spiritually, the historical metaphysically. This means that the reader may encounter an initial confusion, but if he perseveres in the face of the complexities of symbols and thought forms, he eventually discovers a wealth of meaning. Once again the guiding principle is that everything points to and converges upon the eternal reality underlying what Blake called the shadows of life.

The words of Los in The Four Zoas record the moment when Blake got a firm grip on what he sought for himself and for us: "I already feel a World within Opening its gates, & in it all the real substances Of which these in the outward World are shadows which pass away. |FZ7a-86.7; E368| After twenty years in the visionary wilderness that "World within" opened its gates into the mind of the mature artist and poet.

As we have seen, Blake like the biblical writers expressed

the eternal by means of metaphors or symbols drawn from

sense experience. Logical positivists deny meaning either to

the eternal per se or to value of any sort (other than

quantitative); Blake of course stood at the opposite pole.

He despised the mental world of the positivists whom he

knew best: Bacon, Newton,and Locke. They had directed

men's thoughts away from the spiritual and toward the

natural world. In violent reaction Blake refused any

significance to natural events aside from their eternal value.

horses, had developed irony into a fine art and a

popular form of English writing. Irony among other things

requires the use of the intellect. When Blake makes a

statement like, "As I was walking among the fires of

Hell, delighted....", whoever attempts to read this

literally thereby excludes himself from understanding.

But ask the question--what does Blake mean by the fires

of Hell? A few lines before he had said that hell or

evil is "the active springing from Energy". In this way

he responds to the viewpoint of the pious. The knowledge

of irony makes us aware that he disagrees with their

value structure. Blake suggests that the "religious"

most likely would perceive his ideas as evil, so he

ironically accepts their judgment as if to say, "Okay,

I'm evil; if delighting in energy is evil, then I'm evil."

He must have been in contact with some soul deadening

religionists when he wrote this.

A real tail-twister, Marriage of Heaven and Hell has thrilled

thousands of sophomores and helped them to endure

frustrating experiences with "good people". Writing shortly

before Hegel, Blake with his doctrine of contraries

(reason and energy, innocence and experience, love

and jealousy, heaven and hell) vividly displayed

the obverse of every truth which he considered.

He often simply assumed the obvious or conventional

wisdom as a starting point, not bothering to state it

explicitly. Instead he went directly to its opposite,

calling our attention to the dimension of truth buried

on the other side of the conventional. From this dialectic

he finally arrived at a synthesis.

He had a habit of inverting the meaning of the most

sacred words, for example "holiness". For Blake, as for many

others since his day, the holy most often seemed holier than

thou. Sometimes he used the word with an alliterative

adjective such as "hypocritic holiness":

"For then the Body of Death was perfected in hypocritic holiness,"

Milton, Plate 13,(E 107)

Holiness characterizes the self righteous pharisee, who is

most insidious because he judges as non-holy all those who

don't measure up to his standard: "God, I thank thee that

I am not as other men." Holiness of course relates to the

law, which Blake despised for its life denying power.

Furthermore he thought holiness often rather stupid. In

a climactic speech near the end of Jerusalem Los cries:

"I care not whether a Man is Good or Evil; all that I care

Is whether he is a Wise Man or a Fool. Go, put off Holiness

And put on Intellect...." Jerusalem, Plate 92, (E 252)

that the word really means with his sacred line, found at the

end of Marriage of Heaven and Hell: "Everything that lives is holy".

Albert Schweitzer with his "reverence for life", have risen

to that level of vision.

"Religion", like holiness, Blake almost always used as

a pejorative. A deeply religious man, (though he might have

denied it at times) Blake keenly focused on the seedy side

of religion: the greedy priest, the life denying marriage law,

the blasphemous alliance between an established church and

the military, lust of an oppressive crown. "Religion" for Blake

most often conveyed these dire meanings, the sort of thing

that "good people" feel should be slurred over or ignored.

"Elect" and "reprobate" are two words known today primarily by theologians. In Blake's day they were more common. They came into prominence with Calvin's Institutes. The two words basically differentiate the "good people", bound for heaven, from the others. The doctrine of election represented the core or key of Calvinism. Blake adopted the conventional meanings, but he related them, not to the conventional God, but to the God of this World. His elect are those fully conformed to the God of this World. His reprobate is Jesus and others like him who are despised and persecuted by the elect. The "Bard's Song" (Milton, Plate 2, line 22), the first third of Blake's major poem, Milton, concerns the creation of the three classes of men: the Elect, the Redeemed and the Reprobate:

"Of the first class was Satan...."

With such inversions Blake provokes his reader to think more deeply about these terms of value. As you go through the hundreds of pages of Blake's poetry, these and similar terms recur at frequent intervals. The reader who keeps in mind the ironic dimension has a good chance to get the full and vivid impact of Blake's meaning.

No comments:

Post a Comment